Climate misinformation has switched from denialism to attacks on climate solutions. This includes robust attacks on EVs from the fossil fuel sector. Probably not coincidentally, we’re seeing a drop in EV demand, so it’s important to counter misleading and false claims about EVs. That’s why I was concerned when Grist, a normally reliable website on ecological news, ran an article saying that EVs increase tire pollution and therefore aren’t the best solution for decarbonization.

As an EV enthusiast, I took it on myself to look more closely at the data about tire wear provided by “independent” research firm Emissions Analytics. What I found was that although tire pollution is a significant source of emissions, it is not particularly an EV problem. Making this claim not only falsely maligns EVs but makes it harder to do anything about tire pollution.

What Emissions Analytics Concluded

In order for you to understand my objections to Emissions Analytics’ argument, let me summarize their conclusions briefly.

Emissions Analytics researchers compared tire wear on a Kia Niro hybrid-electric vehicle and a Tesla Y. They explain that they chose not to compare the Kia Niro HEV to the Kia Niro battery electric vehicle (BEV) because the Tesla Y is very popular, and they hoped this would give a more real-world comparison. Why they wouldn’t then compare the Y to the best-selling hybrid, Toyota Prius, is not explained.

They drove the cars in convoy to ensure not only that they drove the same distance but drove under the same conditions and driving style. Hopefully they altered the lead car, but this is not stated. Once the cars completed the course, they compared the mass loss from the two cars’ tires and found that the Y’s tires created 26% more particles than the Niro’s: 54 mg/km compared to 43 mg/km. (Note: One ounce per mile is more than 17,600 mg/km, so I’ll stick to the metric measurements here.)

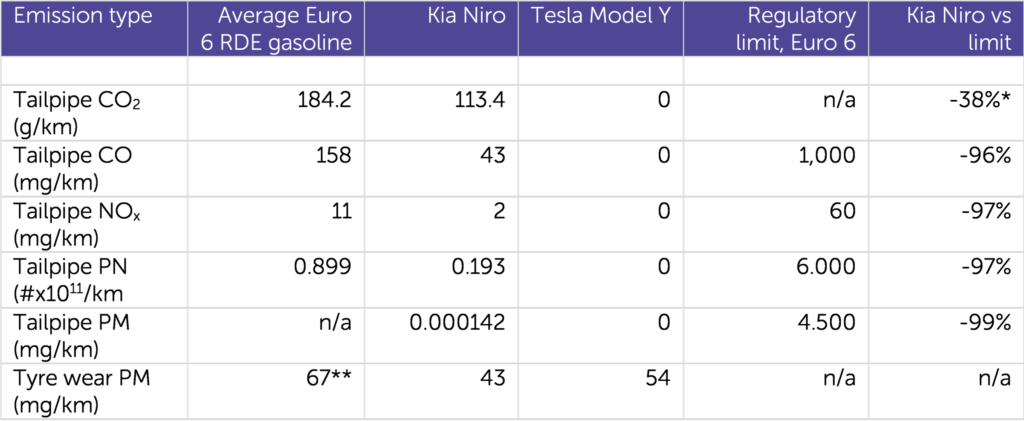

This is the table summarizing tire wear and tailpipe emissions with comparison to an internal combustion engine vehicle (ICEV).

They summarize the point of this evidence:

So, as tailpipe air pollutants were tending to zero from the Kia, it is a fair summary to say that a consumer choosing between switching from a traditional gasoline internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle to either a Kia Niro hybrid or a Tesla Model Y, is weighing up an extra 62% point reduction in CO2 against a 26% increase in particle emissions. However, if full lifecycle CO2 emissions are taken into account, BEVs currently offer around 50% CO2 reduction on average, so in reality the decision to opt for the Tesla is between 12% points of extra CO2 reduction compared to the ICE baseline but 26% more particles.

Do No Harm — Emissions Analytics

Essentially, they minimize the benefits of BEVs vs. HEVs and contrast it against a supposed increase in tire particles. While I want to note that some studies say the life-cycle CO2 reduction from BEVs is 64%, not 50%, I want to show that even if we take Emissions Analytics numbers at face value, they do not show that tire wear is a reason to stop the adoption of BEVs.

Wear Is Mostly about the Tire

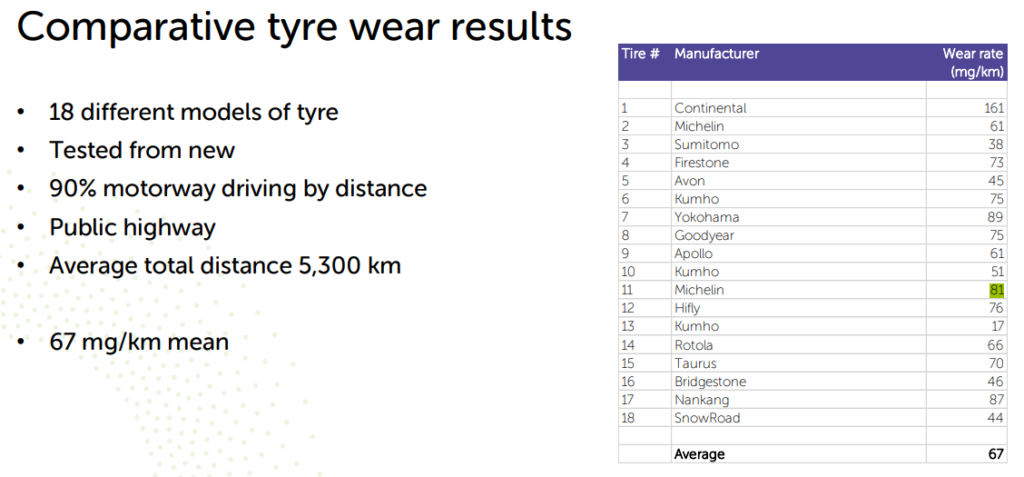

As part of their initial work on tire wear, Emissions Analytics tested 18 different tires on the same vehicle. Below you can see the results, including some basic parameters of the test.

As you can see, there’s tremendous variation in the amount of wear in tires. They range from 17 mg of tire loss per km of driving to 161 mg/km—an almost tenfold variation.

Nor is it simply the tire manufacturer. Emissions Analytics tested three tires by Kumho, with wear values of 17, 51, and 75 mg/km. With this wide variation in tire wear registered with a single vehicle driving the same road, an EV-related effect would have to be huge to stand out against this background noise or you’d have to control tire-related variables very carefully for the effect to show up.

The way Emissions Analytics ran their test doesn’t do this. The tested vehicles use different tires, and without a background test on the specific tires used on the same vehicle, it’s impossible to say how much the difference in wear is related to the vehicle, and how much is just the tires themselves.

It’s also worth noting that this could be the reason why the Kia Niro HEV was chosen. It uses Kumho tires, which included the abnormally low wear value in their data. Meanwhile, the Hankook tires don’t have any background information, but they’re listed by the manufacturer as “performance” tires, which are generally recognized as having higher wear.

Comparing a Heavier, Torquier Car Skews the Test

In asking whether their conclusion is robust, Emissions Analytics says their testing reveals “that the key factors in the relative emissions at the whole-vehicle level are the vehicle mass and torque, the model year and the tyres the vehicle is equipped with.” Not only does this give away that comparing cars with different tires essentially invalidates any conclusions about the vehicles themselves, but it also highlights how much their specific choice of cars set up the conclusion they wanted.

Heavier vehicles wear out their tires faster than lighter vehicles. How much faster? According to Emission Analytics’ own Nick Molden: “A vehicle that’s 1,000 pounds greater in weight will have about 21% more tire-wear emissions.” The weight difference between the Niro and the Y? 1,075 pounds. In other words, weight alone would account for about 85% of the increase in emissions. It’s true that the increase in weight is part of the argument about BEVs vs. HEVs. If they wanted to make this case seriously, they could have compared the Niro HEV to the Niro BEV. The Niro BEV is about 500 pounds heavier, which would, presumably, have increased the tire wear by ~10%.

Another big factor in tire wear is torque. Here the disparity is also great between the two chosen cars. The Tesla Y has 86% more torque than the Kia Niro. Again, for comparison, the Niro BEV has essentially the same torque as the HEV.

Combined with the tire issue, it’s hard to say whether a BEV causes higher tire wear than an HEV for any reason other than the weight—and they both might be a significant reduction from ICEV.

BEVs Might Have Less Tire Wear Than ICEV

Another point that Emissions Analytics doesn’t mention in its conclusion is that it seems that both BEVs and HEVs might reduce tire wear compared to traditional ICEV. When Emissions Analytics tested 18 different tires with an ICEV (a Mercedes C-Class, see table above), they came up with an average of 67 mg/km of tire emissions. That is 24% more than tire emissions from the Model Y in their test.

Emissions Analytics doesn’t give exact specifications for the C-Class they use, but it’s likely that it’s at least 400 pounds lighter than the Model Y, making the reduced tire emissions even more remarkable.

Note: In another article on their website, Emissions Analytics writes, “With typical ICE vehicles emitting 67 mg/km of tyre particles, compared to 81 mg/km for equivalent BEVs, there are some downsides to these heavier vehicles.”

There is no citation for this 81 mg/km figure. If you noticed that the 81 is highlighted in the tire wear table above it’s because I searched their entire site for every instance of “81.” Further, it’s hard to imagine that the Model Y wouldn’t count as an “equivalent BEV” to the Mercedes C-Class. Both are 5-seater sedans. Except for the greater weight and torque of the Model Y, it’s hard to see what might make it not equivalent. If there were robust support for the 81 mg/km figure, why wouldn’t they use, or at least mention it, when discussing the rationale of shifting to HEVs rather than BEVs in their “Do No Harm” article? I believe we have to dismiss this figure until Emissions Analytics provides a source.

What the Data Really Tells Us

Based on the data provided by Emissions Analytics, we can’t say that BEVs inherently create more tire pollution than HEVs. We can say that larger cars with more torque might create more tire pollution than lighter cars with less power. We might also say that both BEVs and HEVs seem to reduce tire pollution compared to ICEVs, although it seems that tire pollution is more strongly linked to tire composition than to the vehicle.

Therefore, we might advocate for smaller BEVs. There are a few options in the US. We already mentioned that the Kia Niro BEV is 500 pounds lighter than the Model Y. Even a Tesla Model 3 weighs about 500 pounds less than the Model Y. The Chevrolet Bolt is typically 700 pounds lighter than the Model Y, and a Nissan LEAF can be as well.

Unfortunately, this is not the trend in the US. Nissan has declared that it is phasing out the Leaf. The Bolt narrowly avoided a similar phase-out.

Meanwhile, many heavy EVs are being released in the US, including the Ford F-150 Lightning. The Ford F-150 is currently the best-selling car in America, and its ICE version already weighs about 5000 pounds, more than any of the vehicles in Emission Analytics’ tire pollution tests. The EV version is 1500 pounds more, so we can expect it to produce 30% more tire pollution than the ICEV.

If we really want to tackle tire pollution, we must first look at tire composition and design tires with less toxic materials that are more durable. Second, we should work on encouraging people to buy lighter vehicles. Finally, I also agree with the Grist piece that we should continue to encourage people to drive less when possible and investigate infrastructure that makes this practical.

There’s also some anecdotal evidence of accelerated wear and tear on BEV tires. It’s hard to know how to take stories like this. There is probably a kernel of truth here, noting that BEVs are heavy and have the torque to accelerate immediately. Some leadfoot drivers who love the jerk from putting the pedal down in their BEV will see a lot of wear. However, I also think these stories are part of a campaign of cherry-picking stories that make BEVs look bad. I think that if we look at a larger data set, we will see that it’s similar to stories about BEV fires. While BEV fires were big headlines, the data suggests that BEVs catch on fire less often than ICEVs and HEVs. I am relatively confident making this statement in part due to my personal experience with BEV tires.

My Personal Experience with Tires and BEVs

I’m not just a BEV enthusiast, I’m a BEV driver. Since October 2019, I’ve been driving a Chevy Bolt. Between the Pandemic and trying to reduce driving whenever possible, my wife and I have put about 35,000 miles on our Bolt. We’ve also had to replace two of the tires. Since the tires are warrantied for about 65,000 miles, this might seem to suggest that BEVs do wear out tires faster.

However, this is more a case of operator error. If BEVs do have a tire wear problem, it’s that the lack of need for regular maintenance makes it harder to remember to rotate the tires. We never rotated our tires, and since the front tires can wear out up to 2.5 times faster than the rear ones, I’d say the jury is still out on the question.

Before the Bolt, we drove a Toyota Prius for 15 years. I don’t know how many tires we went through in the ~160,000 miles we put on the car, but I don’t think any of them lasted the full distance on their tread warranty. However, this seems to be par for the course when it comes to tire warranties.

And I should mention that I do have one more BEV: my custom conversion 1972 VW Super Beetle. It’s a hobby car, though, and it doesn’t get driven much, especially since the Bolt now allows electric driving in comfort. How is its tire wear? One of its tires was made in Yugoslavia, which ceased to exist more than 30 years ago.