Speak Truth to Fire was a completely new type of novel for me. I worked very hard to make it the exact book I imagined it could and should be. I created both personal standards for crafting historical fantasy, and techniques to help myself achieve those standards. Here’s a little bit about how I approached the book and some of the biggest problems in creating my type of historical fantasy.

Riffling History and Fantasy

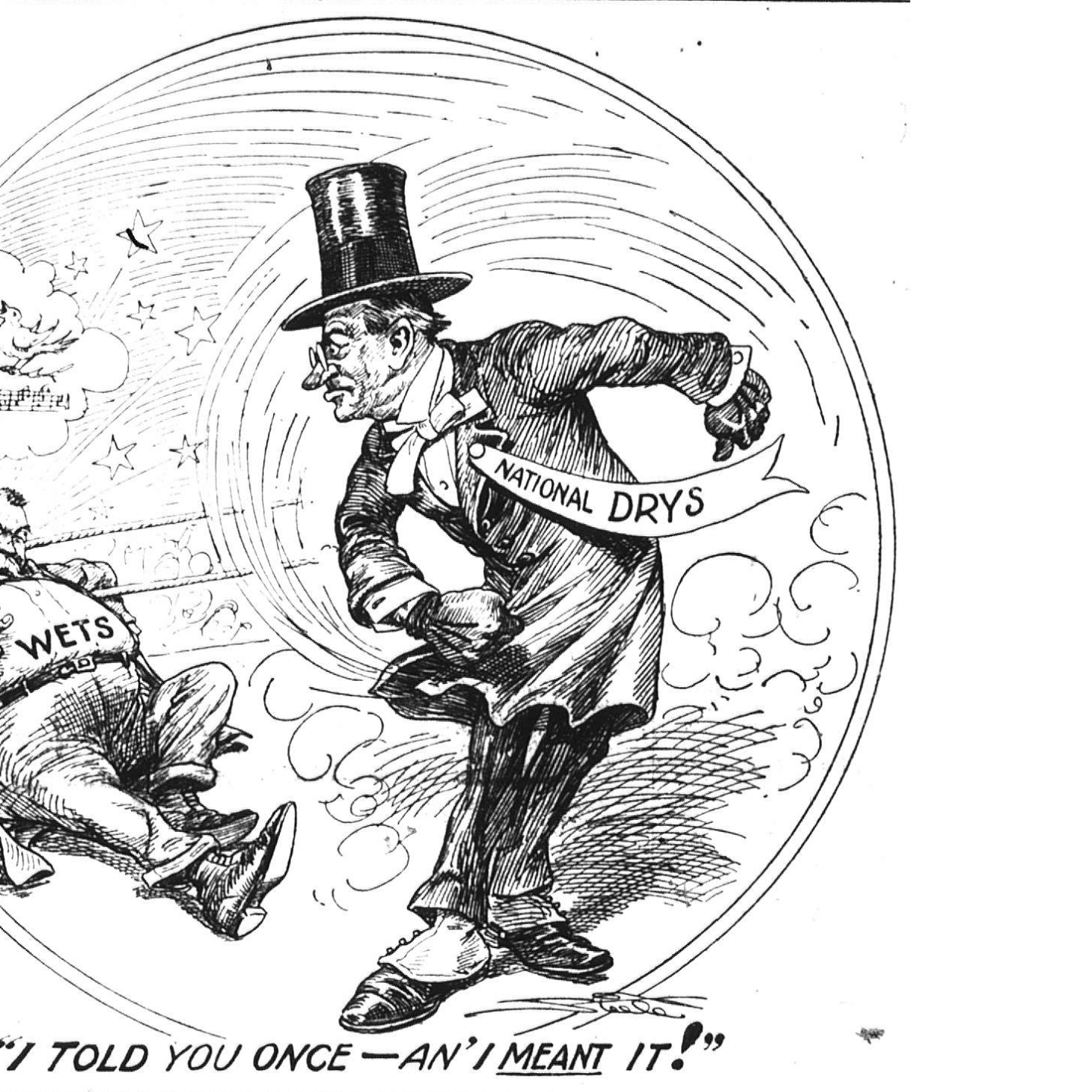

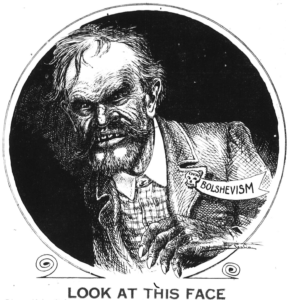

The initial inspiration for the novel came from The Great Gatsby. The last time I read the novel, I was struck by its anti-Semitism. Thinking of it in the context of interwar literature, I wanted to write a story about how racism in America linked to the rise of Nazi Germany. A kind of psychic echo. What I knew about the rise of the Klan in Denver served as further inspiration. I began to build a story, but I felt it needed to be very accurate to carry the thematic weight.

There are many different ways to describe the type of fantasy I wanted to try to write. The most common label would be “hidden fantasy.” In my novel, people live in what is essentially our world, but there are fantastic elements there, if you only know where to look. In the novel, the people who are aware of the fantastic elements might be described as “initiates,” compared to the uninitiated masses who don’t see the things that are happening around them. If they do encounter creatures like demons and forces like magic, they either don’t perceive them or simply can’t internalize what they’ve seen.

I wanted to shuffle together history and fantasy elements so that the two were virtually indistinguishable. Both would feel vibrant and real. They would be part and parcel of a single deck of cards. Most readers wouldn’t know which was which until revealed, either by explicit fantasy elements or well-known historical figures or events.

To enhance this blend I eschewed modern urban fantasy as a model. Instead, I used contemporaneous fiction models. I drew from the hardboiled detective fiction of Dashiell Hammett up to Red Harvest and early H.P. Lovecraft and A.A. Merritt. Trying to blend these two very different literary styles was a huge challenge, but it helped to construct a very distinct novel.

Now I want to look in more detail at how I addressed the challenges of accuracy, anachronism, and representation.

Accurate History

Speak Truth to Fire needed to be extremely accurate or it wouldn’t carry its message. I did considerable research to make sure the people, events, and technology were all historically accurate. Historical accuracy created challenges but also gave me opportunities.

For example, one of the characters is a pilot. He flew in WWI, then as barnstormer after the war. I knew I wanted him to fly around Denver and into the Rockies for some key sequences. But there’s a problem. Like most barnstormers, he flew the Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny.” These planes were produced in huge numbers during the war and after the war they were sold as surplus for very cheap. Here’s the challenge: the Jenny was a terrible plane and had really poor performance, including a ceiling (maximum flying altitude) of about 6000 feet. You can’t do much flying into the Rockies at that altitude! However, a frequent modification of the plane swapped out the engine for a much better one gave the plane a ceiling of 13,000 feet. Not too bad. I just needed to work that into the story.

So that’s a challenge. Here’re some opportunities. John Galen Locke, head of the Klan in Denver for several years after its inception, was a unique character, ready-made to fit into the novel. He was almost like a real-life Batman, with a secret, opulent Klan chamber under his office downtown. He drove a bright red Pierce-Arrow, had two greyhounds, and was an expert knife-thrower. I also utilize a true historical event for the action climax of the novel, one that is terrifying even without the dark fantasy elements. It’s a Klan meeting atop South Table Mountain where Mayor Ben Stapleton fell to his knees and pledged to serve the Klan in exchange for help defeating a recall petition.

To further help with the blend, I tried to make all the fantasy elements, such as magic, true to the period as well. This all comes from contemporary occult literature. The Kybalion, a 1929 Encyclopedia of Occultism (a really lucky find at Goodwill!), and The Secret Teachings of All Ages by Manly P. Hall provide the primary sources for the system of arcane arts and creatures in the novel.

Knowing Your Onions

Another part of accuracy that I strive for is making sure the language is free of anachronisms, i.e. words that people didn’t use at the time and place. This is a very difficult thing to avoid, but I go through a number of steps to minimize their occurrence.

First, I do immersive reading. I try to read exclusively books from the time period before I start writing. Since Speak Truth to Fire is set in the mid-20s

in Denver, I tried to read only books from 1929 and earlier while I was writing it. This helps a lot. You pick up a lot of vocabulary from your reading, and it just naturally flows back out of you. So if you put in the right words, the right words will tend to come out more often.

Then, when I’m going through the novel editing, I’ll check the origin date of any word that stands out to me as being potentially problematic. If it’s technically coined and in usage well enough before the time the novel is set, I let it pass.

Finally, I check any words that my readers flag. In this case, I go one better than just checking the date a word was coined. I run the words through Google Ngram. This is an offshoot of Google Books, which records the instances of words and phrases in all the books scanned for the program. It is a critical tool for tracking down language that just doesn’t belong. Here’s an example of two phrases that my readers flagged for seeming like they didn’t belong: “essential oil” and “vibe.” Based on this data, I felt that “essential oil” was a perfectly reasonable word to use, especially in the context of an arcane sanctuary. For people in the 20s, it would feel like an old word. On the other hand, “vibe” just had no place in the book and was summarily removed.

Honest Representation

For writers today, representation is a bit of a Catch-22. If you don’t represent characters of diverse backgrounds, you’re perpetuating eurocentric patriarchy, but if you do create these characters, you might get in trouble because you’re exploiting people’s image or your characters reinforce negative stereotypes. You don’t want to be limited to just writing the kind of person you are, but you also want to fairly represent all the sociopolitical and ethnic groups you utilize in the book.

This is a challenge, but it’s not an unfair expectation. When you’re writing a novel, you have to take responsibility for your words, and the novelists motto should be the same as the doctor’s: “First, do no harm.”

So, how do I try to walk this tightrope? I generally try to get as representative a slice as I can manage within the confines of the story. I do stick to my wheelhouse to the best that I can. I try to work with experiences that I know and understand. If I am going to have a character, especially a point-of-view character, who isn’t from my time, place, and experience, I always try to read something by a representative of that group, ideally a memoir, but more often a novel. This gives me a sense of how this person might represent themselves and their community, and I work within that space.

The character of Mack is a good example of the delicate balancing act in the novel. I knew I needed a black man in the novel, but wasn’t fully comfortable that I could represent the level of discrimination and hate he would face in this context. Besides, the character that fit him best was the pilot, and the US Army didn’t let black men fly planes at the time. Having him “pass” as white solved these problems. It also offered narrative benefits. First, passing is an experience I’m very familiar with. I felt I could convincingly convey the combination of alienation and shame he would feel. Second, passing was an important part of racial identity in the US in the 1920s. In fact, every character in the novel passes at some point, though for a couple of characters, the reader never knows it, and in one case, the character doesn’t even know it, but they’re going to find out! Between the pilot memoirs and Harlem Revival literature, I probably read more books to build Mack’s character than any other in the novel. In the end, Fighting the Flying Circus by Eddie Rickenbacker, Home to Harlem by Claude McKay, and Passing by Nella Larsen probably had the biggest influence.

I feel he worked out well, but I’m prepared to accept criticism to do better next time. In fact, I’m working on doing better with the sequel. I’m currently in the immersive reading stage and hope to start drafting in the next month or two. Hopefully, the novel will be finished this year for release in early 2022.